Thomas Jiang

About Me

Projects

Writings

Notes

Expert Systems Strategies and Datalog

10 December 2015The final project report Kevin and I wrote for CS252r, a class on static and dynamic program analysis. The project attempts to determine the optimal series of questions to ask a user.

I took this course as a follow up to the introductory classes on programming languages, which I enjoyed. As with many classes, I was unable to dedicate an appropriate amount of time to the class and it shows in the project and the report. On the other hand, the experience of taking it was very helpful. It allowed me to get a sense of what computer science research might look like if I were to go to graduate school and it gave me some greater insight into programming language tools and techniques. Most importantly, I learned that I am not yet mature enough for research and graduate school.

The research project is unimpressive, given that the time we spent working on it was limited. It appears that our project concerns expert systems, a very old concept. Furthermore, our project looks at applying simple game tree algorithms and heuristics to expert system question ordering.

Expert System Strategies Using Datalog Program Analysis

Coauthor: Kevin

Abstract

Expert systems are computer systems designed to solve domain problems in the manner that a domain expert would. These expert systems may query users for facts to help prove the goal, and such systems employ various strategies to determine the order of questions to ask users. Unfortunately, some naive strategies ask unnecessary or irrelevant questions to users, which negatively impacts users’ experiences and reduces the usefulness of these systems. Other systems rely on metarules to inform their question-asking strategies, but these metarules are troublesome to encode and subject to human opinion and error.

This paper describes a domain independent method of automatically generating strategies using program analysis on the encoding of the logic rules. Through the use of heuristics, this method can be used to more easily determine a question-asking strategy that minimizes user-cost.

An implementation of the methods contained here gives preliminary, but encouraging results, for the feasibility and practicality of deriving control flow strategy in this manner.

Introduction

An expert system is typically divided into two components, a database of facts known about the world and a domain specific knowledge base. This domain specific knowledge base can be encoded as sets of logical rules. These rules generally take the form:

\[ \text{IF } \alpha_1 \land \alpha_2 \land \ldots \land \alpha_n \text{ THEN } \sigma \]

where each \(\alpha\) represents a logical statement relevant to the problem domain and \(\sigma\) represents the logical statement that is true if \(\alpha_1\) through \(\alpha_n\) are true. Such assertions are naturally amenable to being represented in logic programming languages such as Prolog or Datalog.

For instance, the following rule is in this form: IF the student has taken CS51 \(\land\) the student has taken CS152 THEN the student can take CS153. A fact in the database of facts about the world might take the form: Student X has taken CS51.

An expert system then deduces conclusions, via its inference engine, based on its database and the knowledge base. In a backward chaining expert system, the inference engine starts with a logical goal to prove, then uses the inference engine to derive the necessary conditions that would lead to that goal. Finally, it checks to see whether those conditions are true to determine whether the goal can be reached. This is opposed to a forward chaining expert system, which starts with the facts and applies rules until it can derive a conclusion. In backward chaining expert systems, if the system does not have a necessary fact in order to derive the conclusion, it may query a user in order to receive new information.

In systems with a large set of rules and many unknown facts about the world, there is the difficulty of determining what order to ask the user for facts about the world. In some inference engines, such as Prolog based expert systems, the strategy, or ordering of questions, is determined by the encoding of the rules themselves.

In such systems, if the encoding of the rules is not done with care, the system may ask many irrelevant questions to the user which increases the cost of using the system. In order to find the best strategy of asking questions, one might consider every possible order of asking questions and the possible answers that could be given. By finding the cost of each strategy, one could find the best possible strategy. Unfortunately, the number of strategies grows factorially making such a search strategy infeasible.

In this paper, we present a set of heuristics based on program analysis of Datalog that can be used to inform expert system strategies. These heuristics can be used to inform the naive search of possible strategies by reducing the number that need to be searched or they can be used to generate a strategy without conducting the naive search. These heuristics can be automatically computed through program analysis on the domain knowledge. In this paper, we explicitly consider expert system whose knowledge bases are written, nonrecursively, in the logic programming language Datalog. Datalog was chosen because it is sufficiently expressive for the basic tasks at hand, while still being easy to analyze.

Motivating Example

This research was motivated in part by the DataTags project, which aims to help researchers share data by aiding in the navigation of the complex laws that govern the sensitive data sharing. As part of the workflow, researchers sharing data sets are asked a series of questions about their data. For instance, ``Do the data contain health or medical information?” Based on the answers, the data will be tagged appropriately and the researcher will be given information about the guidelines governing the sharing of their data set, e.g. storage, transit, and access requirements.

Currently, the DataTags questionnaire is encoded in a domain specific language that combines domain knowledge (knowledge about the laws governing sensitive data) with control flow logic (knowledge about the order to ask the questions). This representation of the questionnaire makes the questionnaire more difficult to maintain as laws change and the questionnaire grows in size and scope. In addition, as a very stateful system, it is very difficult to understand in the first place.

Separating the domain specific knowledge from the control flow logic allows each to be modified cleanly and independently. As such, project stakeholders wanted to explore the encoding of just the domain logic as a Datalog program. But this then necessitates the independent production of that control flow logic. Thus, this a clear example of how the research question at hand may be applied to scenarios in which the domain knowledge is clear but the appropriate control flow is not.

Organization and Contributions

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 formalizes the aforementioned problem statement. Section 3 describes a possible approach to the problem (envisioning it as a game tree) as well as some naive searching techniques. Section 4 introduces the PredicateDAG and the heuristics we developed with the use of that tree. Section 5 examines the preliminary results of these heuristics, both in their performance relative to ground-truth, and their ability to speed up the tree search. And finally, Sections 6 and 7 present related and future work, and conclude.

Our contributions are the following:

- A game-theoretic approach to the separation of control flow and domain logic for surveys such as this one and related system.

- To our knowledge, the first attempt to derive this control flow logic automatically from domain logic encoded in Datalog.

- The identification of several useful heuristics based on Datalog program analysis.

Problem

We begin with a clean description of the problem, then discuss some simplifying assumptions that we made here. These become relevant later in Section 5: Preliminary Results.

Definitions

Let us define the following:

- \(\textbf{Question}\): the questions that the program may ask. We also need a mapping from these questions to a set of Datalog predicates (possible responses).

- \(\textbf{Trace} = \textbf{Question}^*\) to represent the questions that have already been asked at any given point.

- \(\textbf{Database}\): Datalog programs (both unit clauses and predicates). The database of Datalog rules should always include rules for a special predicate \(\texttt{decided}\), the derivation of which indicates our survey is complete. For the purposes of heuristics that follow,we restrict ourselves to non-recursive Datalog programs, in which predicates all have arity less than or equal to one.

- A function \(Cost: \textbf{Trace} \to \mathbb{R}\). We require that this function be monotonic. In particular, if \(t_1, t_2 \in \textbf{Trace}\) and \(t_1 = t_2q_1q_2\ldots\) then \(Cost(t_1) > Cost(t_2)\). We may also consider more specific cases of the cost function later.

- A set \(W\) of all possible states of the world. We think of the world as holding all the answers to our questions. We also define \(\mathcal{W}\), a distribution on possible states of the world. We will draw a particular world state, \(w\), from this distribution.

- A function \(Ask: W \times \textbf{Question} \to \textbf{Database}\) that represents asking the user for information and returning some Datalog predicates.

- A function \(Strat: \textbf{Database} \times \textbf{Trace} \to \textbf{Question}\). This is what we are seeking to solve for. Given a database representing the facts we know and the inference rules we have, and a trace of the questions we’ve asked so far, what question should we ask next?

- A function \(Interact:\)

Interact(W, db, strat)

tr = []

while db does not imply decided do:

q = strat(db, tr)

tr = tr + q

db = db + ask(W, q)

od

return trGiven these definitions, what we desire is the strategy such that minimizes \(E_{\mathcal{W}}[Cost(Interact(W, db, strat))]\). Basically, we would like a strategy that minimizes the expected cost of concluding \(\texttt{decided}\) given what we know about the world.

2.2 Assumptions

Unfortunately, we were unable to be fully general with respect to the distribution of world states or cost functions in this initial exploration of the problem. Instead we assume while computing trace costs that the cost is just the number of questions asked. Furthermore, we assumed that there were only two answers to each possible question, \(\texttt{yes}\) and \(\texttt{no}\), each with probability \(0.5\) irrespective of the question or previously asked questions.

In some senses, these are quite restrictive assumptions. Indeed they omit much of the problem’s complexity. But, they still allow for an interesting exploration of the problem, as we shall see. Addressing some of these assumptions figures prominently in Section 7: Futher Work.

3. Naive Solutions: Searching

In this section, we conceptualize the problem as a game tree of sorts, and explore search-based solutions to our problem.

3.1 Game Tree

We can conceptualize this problem as a game between two players: the survey-asker and the survey-taker, who alternate turns. Let us denote nodes in the tree where the survey-asker is about to choose a question as \(\textit{SurveyNodes}\), and points where the taker is about to return an answer as \(\textit{WorldNodes}\). The game ends when the asker is able to conclude \(\texttt{decided}\) given the information provided by the taker up until that point. The survey asker then incurs the cost of the trace up until that point.

3.2 Naive Search

From this GameTree, a naive search comes quite naturally. At each SurveyNode, we consider all possible actions of the asker, that is, we consider asking all questions that have not yet been asked. And at every WorldNode, we consider all possible responses of the survey taker. At the leaves of tree, costs are calculated according to the cost function. Costs propagate up the tree quite naturally. The cost of a WorldNode is the weighted average of its children’s costs (weighted by the probability of each answer). The cost of a SurveyNode is the minimum of its children’s costs, with the question that produced that node being the best question at this SurveyNode. The computation of this total GameTree then gives the desired completed strategy, as it produces the cost-minimizing question at every possible point.

Unfortunately, this search has incredibly terrible time complexity. In the worst case, it must consider all \(n!\) permutations of questions, and for each permutation, the \(2^n\) possible sets of answers to those questions, and thus is at least \(O(2^nn!)\) (assuming constant time for the Datalog engine).

3.3 Alpha-Beta Search

Alpha-Beta Pruning or Alpha-Beta Search is a variant on the minimax search algorithm that is commonly used on game trees to determine the best next move. At a high level, Alpha-Beta pruning searches the tree one move at a time. If it determines that a move (for either party) is worse than a previously examined move, it stops evaluating the remaining possibilities that could result of taking that move, effectively pruning part of the game tree. If the moves are searched in the optimal order, the effective branch factor of the tree is reduced to its square root, speeding up the search significantly.

There are several caveats when applying Alpha-Beta pruning to the problem at hand. Most importantly, Alpha-Beta assumes that the two players are antagonistic. That is, one player is trying to minimize their own cost, while the other player is trying to minimize it. Bringing it back to the survey example, this would be like the survey asker always returning back the least helpful answer to us (hoping to prolong the survey and their time with the survey asker).

This is slightly different from the problem as conceptualized above, which assumes that the survey taker is non-deterministically choosing a possible question response from some distribution. We include this section here for two reasons. First, we believe that Alpha-Beta search can be modified in a way that still increases efficiency without making this bad-world assumption. And second, even this related problem that assumes a antagonistic world is an interesting one to consider.

Within the framework necessitated by Alpha-Beta search, there are some further caveats. Because Alpha-Beta pruning does not evaluate the entire game tree, in order to determine the next best possible move, it may necessary to perform the algorithm each time the state of the world is changed (if the world returns back an answer that we have no yet searched). Furthermore, because Alpha-Beta pruning still grows factorially with respect to the number of questions, it may be impossible to fully compute Alpha-Beta within a reasonable amount of time. As a result, it may be necessary to develop a heuristic to evaluate each game state, regardless of whether decided can be derived at that game state. This is an approach commonly taken in game engines for Chess, for example. This problem is not addressed in this paper. Finally, Alpha-Beta pruning can be just as slow as the Naive Search if the ordering of the moves searched is suboptimal. This leaves room for some sort of strategy being used to determine the order of questions to be searched using Alpha-Beta pruning.

4. Heuristics

Given the computational difficulty of deriving the optimal solution using the aforementioned naive search approach, we explore here several heuristics that may ameliorate the problem. First, they can be used to speed up the naive search to something that is more computationally tractable. And second, these heuristics may be used to write a question-asking program that hopefully does a reasonably good job of approximating the optimal strategy. We could even imagine doing this dynamically, computing the best next question to ask in response to user input as the user takes the survey. This is feasible as these heuristics are generally computationally lightweight, especially when compared to the previous naive searching.

In this section, we first define the PredicateDAG, and then describe the heuristics that operate over this graph as well as their usefulness for our purposes.

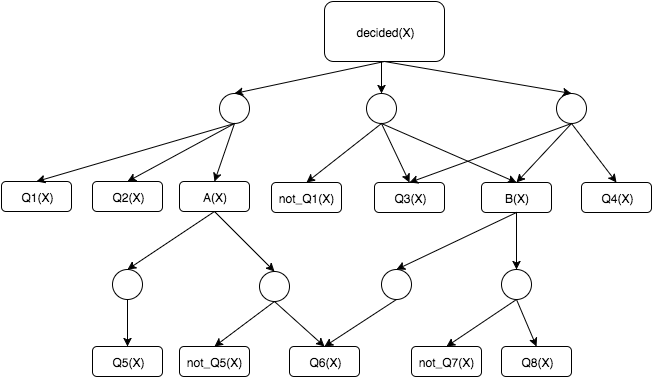

4.1 Predicate DAG

What we refer to here as the PredicateDAG is a variation of “And-Or Trees.”. In this particular variation, we are using it to represent the Datalog programs we are concerned with. The PredicateDAG is made of two types of nodes, OrNodes and AndNodes, which strictly alternate (there are no edges between OrNodes or between AndNodes). An OrNode represents a predicate in the Datalog program, for example \(\texttt{decided}\). As its name implies, it is true if any of its children (AndNodes) are true. AndNodes represent bodies of Datalog rules. Again, as their name implies, they are true only if all their descendents (OrNodes) are true. Note that OrNodes can have multiple parents, if that predicate is used in a variety of rules, but AndNodes have only one parent, as they each correspond to exactly one rule in this implementation. “Leaves” (nodes with no children) in the PredicateDAG correspond to those predicates which are the result of asking questions. Our restriction to non-recursive Datalog programs ensures that this graph is acyclic, though note that it is not a tree. For example, multiple AndNode children of an OrNode may refer to another OrNode, as seen in Figure 1.

decided(X) :- Q1(X), Q2(X), A(X).

decided(X) :- not_Q1(X), Q3(X), B(X).

decided(X) :- Q3(X), B(X), Q4(X).

A(X) :- Q5(X).

A(X) :- not_Q5(X), Q6(X).

B(X) :- Q6(X).

B(X) :- not_Q7(X), Q8(X).

The dynamic updating of the PredicateDAG is quite straightforward. When we receive a piece of information from the world, we need to make one OrNode true, and one false. For the OrNode marked true, we examine their parents and remove this child. If that leaves them with no children, then the AndNode’s parent is then recursively marked true. For the OrNode marked true, we examine each AndNode which is now false. If the parent of that AndNode has only this one child, then it is recursively marked false.

These updates are made according to a topological sorting of the graph, so as to not require multiple operations at any given node.

4.2 Must Ask Questions

This first heuristic is perhaps the most basic. A question must be asked if, given the current set of facts, all possible ways of concluding decided include the answer (whether positive or negative) to a specific question. The computation of this set is quite straightforward. We compute this MustAsk set for every node in the DAG. At the leaves (OrNodes denoting question answers), the set is of course just the singleton set corresponding to that question. From the leaves, this information is then propagated upward (in topological order). The MustAsk sets of AndNodes and OrNodes are then computed by taking the union and intersection of their children’s sets, respectively. The MustAsk sets of the root \(\texttt{decided}\) OrNode represent our desired set.

4.3 Dependency

The dependency heuristic can be defined in a way similar to the MustAsk heuristic. Question A is dependent on Question B if, for every possible trace that concludes decided while using Question A, Question B is also used. Because there is no trace concluding decided that only involves Question A, this suggests that when considering possible traces in our GameTree, we should only consider traces that order Question B before Question A. This will reduce the number of traces that we must search over.

This heuristic can be computed by an upwards propagating algorithm that starts at the leaves of the PredicateDAG. Every node calculates a mapping from questions to sets of not dependent questions. At the end, the mapping from questions to not dependent questions can be flipped to determine dependent questions.

Starting from the leaves, which are OrNodes that represent single questions, each leaf maps every question that is not itself to the singleton set containing its own question. This represents that, at this leaf, no other questions are dependent on this question. This information is propagated up the DAG, as explained below.

Each AndNode creates a new mapping by iterating through each of its children. For each question, the AndNode will determine whether any of its children map that question to the empty set. This means that one of its children has a trace that is dependent on that question. If so, the AndNode will map that question to the empty set, representing that it is dependent on that question. Otherwise, if none of the children map the question to the empty set, the AndNode maps the question to the union of the sets its children have that question mapped to. At any OrNode that is not a leaf, the OrNode will simply map each question to the union of the sets of questions that its children have that question mapped to.

Once all of this information is propagated to the root node, we now know, for every question, the set of questions that are not dependent on it. Thus, in order to find the set of questions that \(\textit{are}\) dependent on a question, we can take the set difference of the set of all questions and the set of questions that are not dependent with that particular question, producing our desired result.

Because the dependency status of two questions may change as more facts about the world are known and the PredicateDAG is updated according, the dependency heuristic can be easily recalculated upon receiving new facts.

4.4 Codependency

The codependency heuristic is a specialized case of the dependency heuristic. Question A and Question B are codependent if Question A is dependent on Question B and Question B is dependent on Question A. This information gives us more specificity than the dependency heuristic. The codependency calculation relies on the same not dependent information calculated by the dependency heuristic. After calculating the not dependent information, one can simply check to see if two questions are codependent by seeing if they each dependent on the other.

4.5 Counting

Absent the ability to use one of the above heuristics, this is perhaps the simplest thing to do. The leaf nodes, unsurprisingly, consist of one mention of the question that corresponds to the OrNode’s predicate. Moving up the DAG, we just sum at every level the mentions of questions at the children. At the root \(\texttt{decided}\) node, the best question to ask is then just the one with the most mentions in the program. This is meant to be an approximation of value, the idea that a question whose answers show up often in the DAG is likely higher value, and should be asked sooner rather than later.

4.6 Overall Heuristic Strategy

Our overall heuristic-based strategy then does the following:

- If a previous iteration indicated that some questions must be asked next, ask one of those.

- Otherwise, if there is at least one question that must be asked, arbitrarily choose one of them to ask.

- Otherwise, consider the question with the highest count. If this question is dependent on some other questions, ask one of those questions, and remember any other depended-on questions as to be asked next. If this question is codependent with any other questions, ask it, and remember its codependent questions as to be asked next. Otherwise, just simply ask this question.

4.7 Search Optimization

These heuristics can also be used to optimize our search space by cutting down the number of children added to SurveyNodes.

We make the following optimizations:

- If a previous asked questions indicated that some questions must be asked next, only search asking that question.

- Otherwise, if there is at least one question that must be asked, only search asking one such question.

- Otherwise, search asking all possible questions with the following modifications. If two or more questions are codependent, only ask one of them now, and remember the others in the set as to-be-asked-next. If a question is dependent on another question, do not explore asking it now.

These serve to significantly shrink the branching factor of the GameTree, by greatly decreasing the number of possible next questions as some SurveyNodes. This is effectively cuts down the permutation factor of $n!$ in the aforementioned runtime.

5. Preliminary Results

The above heuristics and game search were implemented in Java, so as to make use of the Datalog engine written by Aaron Bembenek. The assumptions that we have made regarding cost functions and probability distributions (mentioned in Section 2.2) render a comprehensive and principled evaluation difficult. In addition, with the multitude of possible surveys, it’s challenging to enumerate a principled representative sample. As such, the below results should be considered less of a comprehensive evaluation, but instead as a proof-of-concept validation.

We were able to run the full brute-force search as well as our heuristic over several small-size surveys that we attempted to make diverse in structure:

- For highly determined surveys (e.g. when there is always exactly one MustAsk question), the heuristic and optimized search both perform admirably, returning the expected ordering of questions in an efficient manner.

- In general, the heuristic-based strategy performs quite well on our examples. For some of these highly determined ones, it attained identical expected cost, and in the worse example, performing 19% worse (in expected cost). These surveys roughly correspond to certain encodings of flowcharts.

- The heuristics can be quite effective in cutting down the number of nodes that need to be explored in the game tree search. For example, on one survey it cut the number of such nodes from 35 to 4, and in another, the optimized search was able to return after searching 2300 nodes while the non-optimized version exceed Java’s heap memory.

While certainly not comprehensive, these results indicate that these heuristics can be effective in practice.

6. Related Work

In traditional expert systems, concerns about the ordering of questions have generally been left to the expert system designer and domain expert. For instance, some systems, such as ones encoded in Prolog, might perform the following: (a) all (relevant) rules are tried and (b) all rules whose left-hand sides match the case (and whose right-hand sides are relevant to problem solving goals) have their right-hand sides acted upon. But under different circumstances, other strategies would be more appropriate.

For instance, the early expert system MYCIN, relied on metarules to help the inference engine determine which question to ask next. Metarules are rules of the same IF/THEN form as the knowledge base rules, but instead of reasoning about the expert domain, they reason about the knowledge base rules themselves.

These metarules are explicit encodings of strategy knowledge. The explicit encoding of knowledge was recognized as an important design consideration for expert systems. However, the creation and use of MYCIN and other subsequent expert systems demonstrated that it was extremely difficult to get the necessary knowledge in order to create expert systems and other knowledge-based computing systems. This problem, known as the knowledge acquisition bottleneck or knowledge-engineering bottleneck, has been examined from a variety of angles. As a result of this bottleneck, it is difficult and time consuming to program expert systems with correct and helpful metarules.

Thus, some focus has been turned towards dynamically creating metarules instead of having the domain expert and engineer explicitly encode them. For instance, neural networks have been used to reduce the number of rules that are fired in order to reduce the number of questions asked. Others have taken a probability-based approach, relying on Bayesian reasoning to determine possible best questions. Unfortunately, these approaches (like our naive search) can quickly become intractable, and often discard important information regarding the rules themselves.

To our knowledge, our work is the first example of this reasoning regarding question-asking that is done through program analysis of the rules, specifically in this case an analysis of Datalog.

7. Future Work

While this report represents a good first start with interesting preliminary results, it has also led to many interesting questions that we hope to explore further.

First comes our assumptions with respect to the probability distribution and cost function. As mentioned previously, some of our heuristics cease to be sound when the cost function is no longer merely the number of questions asked. It might be interesting to explore other cost functions that are more expressive, but perhaps with still sufficient structure to drive efficient searching. For example, one can imagine a modularly structured cost function, in which the permutation of certain sets of questions relative to one another matters, but where the sets can be arbitrarily interleaved with equivalent cost. In addition, the current analysis neglects any consideration of probability distributions.

Next, we would like to explore possible further heuristics. In a world where our cost functions are more general, for example, asking codependent questions in different orders may produce different costs, and we might like to determine an optimal ordering. In addition, our currentheuristics do not consider probability in anyway. Armed with knowledge of this distribution, or even an approximation of it, we should be able to derive additional heuristics that take this information into account.

Also, as we mentioned previously, it would be interesting to consider using these and other similar heuristics in an Alpha-Beta-esque search, both for evaluating ``game states” as well as determining the order in which to search node descendants (which greatly affects the algorithm’s performance).

Finally, we would like to consider extensions to the Datalog language itself. First, we would like to explore possible annotations to these Datalog programs, that might express, for example, dependency, or other relationships between questions. While not required, the ability to include these annotations might give the survey writer greater control in determining the used heuristics and the efficiency of the GameTree search. In addition, we would like to consider theoretical extensions of the Datalog that would allow for full encoding of the upper-bound and lower-bound relationships we encountered when examining the DataTags survey. Basically, can we cleanly expression assertions such as “potential data harm is no worse than level X?” We believe that the use of Datalog hypotheticals may be one avenue toward achieving this expressivity.

8. Conclusion

This paper advances a number of techniques for determining an optimal control-flow when given piece of domain logic encoded in Datalog. These include a naive search of the game tree, as well as several heuristics that can be used as a strategy in themselves, or in tandem with the naive search as an optimization. Though results are still quite preliminary, they are promising, and show that such approaches based on program analysis of Datalog may in fact be practically useful.

Acknowledgments

We are first indebted to Professor Stephen Chong for his guidance and supervision of this work over the last year. And also to Aaron Bembenek for his help and support with respect to his Datalog engine. And finally to Michael Bar-Sinai, who provided a helpful introduction to the DataTags project.

References

- Datatags. URL http://datatags.org/.

- A. Bembenek. Datalog engine final report, 2015.

- R. Bogacz and C. Giraud-Carrier. Learning meta-rules of selectionin expert systems. Technical report, Bristol, UK, UK, 1998.

- A. J. Bonner. Hypothetical datalog: Complexity and expressiblity. In M. Gyssens, J. Paredaens, and D. V. Gucht, editors, ICDT’88, 2nd International Conference on Database Theory, Bruges, Belgium, August 31 - September 2, 1988, Proceedings, volume 326 of Lecture Notes in Computer Science, pages 144–160. Springer,1988. ISBN 3-540-50171-1.

- B. G. Bushanan and E. H. Shortlife. Rule Based Expert Systems: The Mycin Experiments of the Stanford Heuristic Programming Project. Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, 1984.

- G. Carenini, S. Monti, and G. Banks. An information-based bayesian approach to history taking. In Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Medicine in Europe: Artificial Intelligence Medicine, AIME ’95, pages 129–138, London, UK, UK, 1995. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-60025-6. URL http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=648153.751268.

- E. Davis. Constrained and/or trees, 2002.

- B. R. Gaines. An overview of knowledge-acquisition and transfer.International Journal of Man-Machine Studies, 26(4):453–472,1987. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7373(87)80081-0.

- D. Knuth and R. W. Moore. An analysis of alpha-beta pruning.Aritificial Intelligence, 6(4):293–326, 1975. doi: 10.1016/0004-3702(75)90019-3.

- D. Merritt. Building Expert Systems in Prolog. Amzi! inc., Lebanon, Ohio, 1989.